The Myth of the Continental Dollar: Part Two

Originally published in The Numismatist, July 2018

The circumstantial case surrounding the creation of this popular issue collapses under the weight of new evidence.

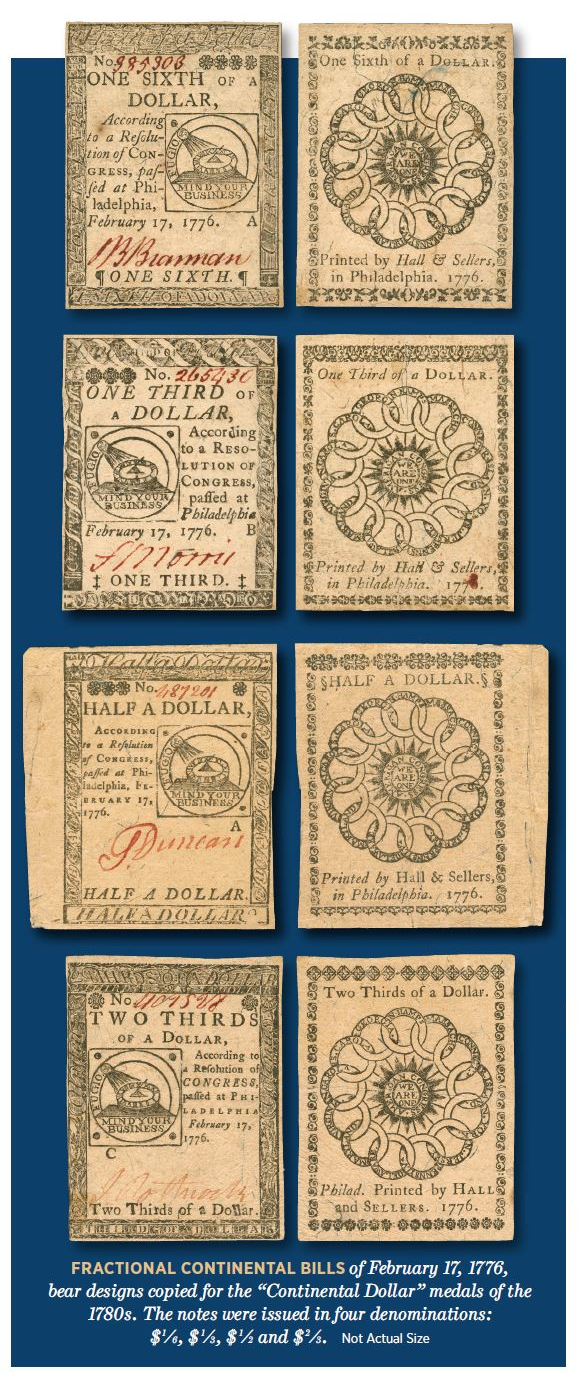

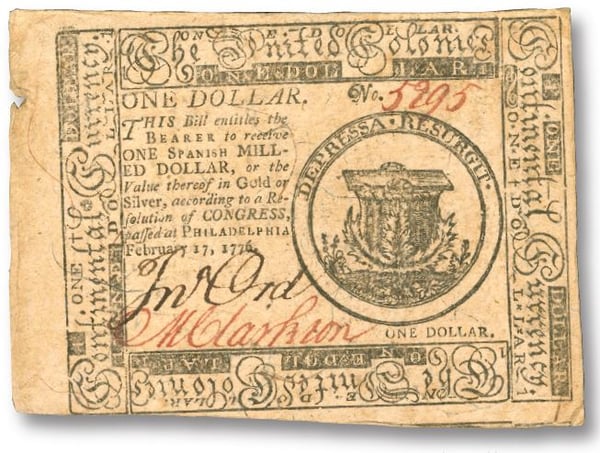

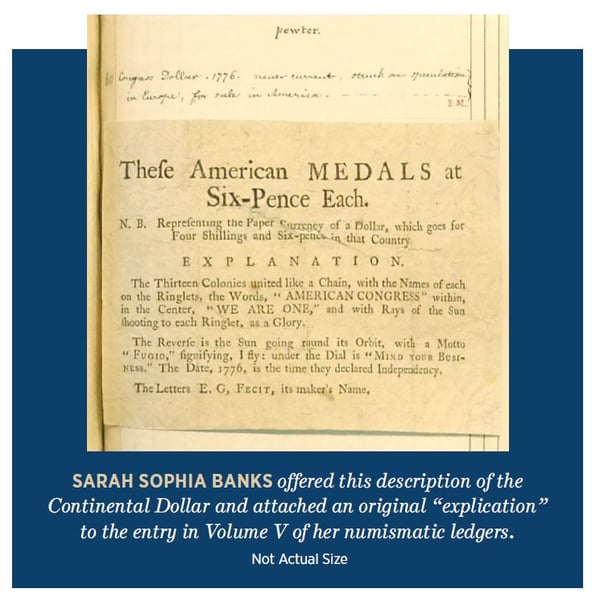

In the first installment of this study regarding the 1776 metallic “Continental Dollar”1 (The Numismatist, January 2018, p. 48), the relevant personalities and documents of the period were allowed to speak for themselves. Taken strictly at face value, these words tell us that the pieces were first produced in Europe around 1783 as inexpensive commemorative medals. Their designs, aped from the fractional Continental Currency bills of February 1776, show an unknown creator’s intent to make them appealing, and therefore salable, to those with an interest in the nascent United States.

Now that the foundation on which the Continental Dollar has long stood is irreparably fractured, many of the commonly accepted “facts'' must be reassessed with open minds and fresh eyes. It is my hope that the following arguments will help separate wheat from chaff, so that we might be able to see the Continental Dollar for what it really is, not what folks have long pined for it to be.

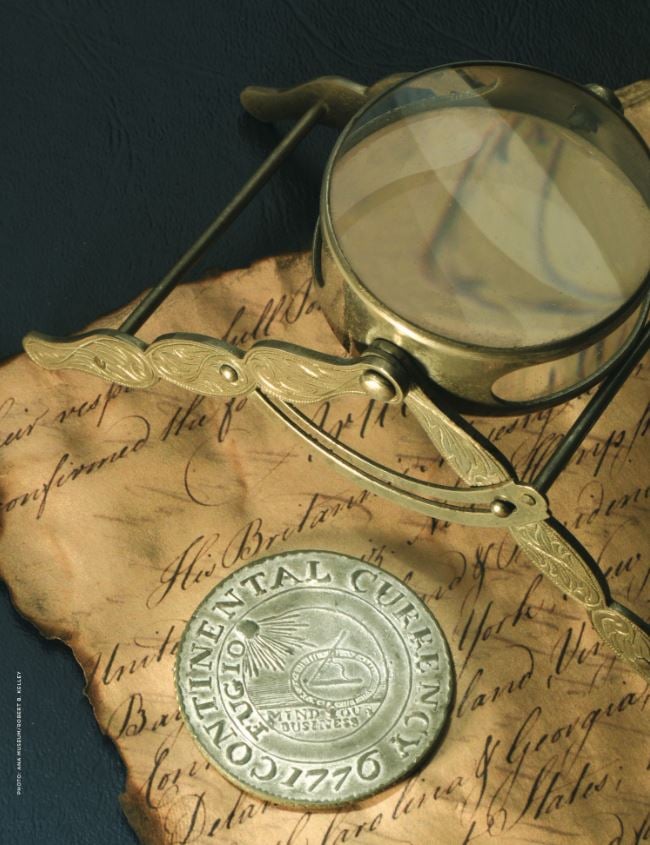

▲ Photo: ANA Money Museum/Robert B. Kelley

Did We Really Know What We Thought We Knew?

How did we get to a point where so many accepted the Continental Dollar as a genuine example of American Revolutionary currency? One obvious part of the problem is its design. Couple “1776” with the Franklinesque “Sundial” and “Linked Rings,” and you are sure to trigger numismatic lust. The naked visual appeal of the Continental Dollar has been fooling almost everyone, from schoolkids to the most dedicated numismatic researchers, for decades.2

▲ Photos: The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation/Gift of the Lasser Family (2003-94)

Ninety-nine years after the ostensible date on these metallic pieces, numismatist and author Sylvester Sage Crosby3 (pictured right) plated the Continental Dollar and described the physical traits of a few specimens struck in different metals. He then concluded with a transcription of Bishop Richard Watson’s 18th-century report, generally acknowledged as the first English-language description of the coin to appear in print. Included therein was an erroneous passage about the pieces being issued by Congress, a point refuted by academician Josiah Meigs in 1788.4 Accepting the issue for what it appeared to be, Crosby took the opportunity to mention that they were “not of extreme rarity, neither are they very common.” During the era of the Centennial, when prominent American numismatists were willing to accept a few 1776-dated oddities as genuine, it seems the Continental Dollar wasn’t raising any eyebrows.5

Ninety-nine years after the ostensible date on these metallic pieces, numismatist and author Sylvester Sage Crosby3 (pictured right) plated the Continental Dollar and described the physical traits of a few specimens struck in different metals. He then concluded with a transcription of Bishop Richard Watson’s 18th-century report, generally acknowledged as the first English-language description of the coin to appear in print. Included therein was an erroneous passage about the pieces being issued by Congress, a point refuted by academician Josiah Meigs in 1788.4 Accepting the issue for what it appeared to be, Crosby took the opportunity to mention that they were “not of extreme rarity, neither are they very common.” During the era of the Centennial, when prominent American numismatists were willing to accept a few 1776-dated oddities as genuine, it seems the Continental Dollar wasn’t raising any eyebrows.5

▲ Photos: ANA Archives (Crosby) & The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation/Gift of the Lasser Family (1994-210, 40, 45, 49 & 54)

Almost 75 years later, the issues remained mainstays of the colonial-coin domain, though doubts were starting to bubble up. One collector who questioned the wholesale legitimacy of the Continental Dollar was Damon G. Douglas, who wrote this in the April 1948 issue of The Numismatist 6:

Completely ignored by Congress, it was produced, according to Du Simitière’s 1784 notebook, in London probably as a satire on the paper currency that was becoming a synonym for worthlessness.

While Douglas was correct about du Simitière’s words, the bit about the issue being “satirical” is purely speculative on his part. Since Pierre Eugene du Simitière (1737-84) had intended to illustrate the Continental Dollar in his celebratory history of the United States, we can be sure he didn’t see it as sardonic.7

Douglas’ words were taken seriously by 38-year-old Eric P. Newman (pictured), causing the great numismatist to return an About Uncirculated brass Continental Dollar to James Kelly, the dealer who had offered it on approval for $145. In rejecting the piece, Newman wrote on July 25, 1949:

I am sorry that I am returning the Continental dollar in brass. I am still interested in it, but because of recent research of others the evidence points to the fact that these may be satirical pieces made in England, after the Revolutionary War and are not contemporary pieces.

Something changed Newman’s mind over the course of the next three years. His landmark monograph, “The 1776 Continental Currency Coinage,” was published in the July-August 1952 issue of The Coin Collector’s Journal (No.144).

Always advancing the ball down the field, Newman continued his research, which led to his article “The Continental Dollar of 1776 Meets Its Maker,” published in the August 1959 issue of The Numismatist. Above the title of this study is posed the frank question, “Does circumstantial evidence solve this problem?” The fact that we are having this discussion almost 60 years later shows the circumstantial case Newman made in 1959 has compounded the problem, not resolved it.

Always advancing the ball down the field, Newman continued his research, which led to his article “The Continental Dollar of 1776 Meets Its Maker,” published in the August 1959 issue of The Numismatist. Above the title of this study is posed the frank question, “Does circumstantial evidence solve this problem?” The fact that we are having this discussion almost 60 years later shows the circumstantial case Newman made in 1959 has compounded the problem, not resolved it.

Newman began his argument by correctly noting that the Continental Currency $1 bill, included in all four emissions authorized between May 1775 and May 1776, had been omitted from every subsequent release through the September 1778 issue. It reappeared as the lowest denomination of the January 1779 issue, and the Congressionally guaranteed bills issued in the names of eight individual states during the spring and summer of 1780. Newman then suggested that this paper-dollar void was intentionally created to make room for a circulating metallic version—one completely absent from the voluminous records of the Continental Congress.

▲ Photos: ANA Archives (Newman) & The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation/Gift of the Lasser Family (1994-210, 58)

On the surface, Newman’s theory of a whitemetal, dollar-shaped coin, struck on the down low in Revolutionary America to serve as a substitute for the paper version, seems plausible. Bringing his theory forward, we can logically gauge the number of pewter dollars thereby required by looking at the size of the gap in $1 bill production. And this is where the entire notion runs off the rails.

In studying the actual printing of lower-denomination Continental bills8, we see that the quantities of each were the same.9 During the time the $1 bill was produced (between May 1775 and May 1776), the exact same numbers of $1, $2, $3 and $4 notes were generated. When the paper $1 reappeared in 1779, it again was printed in quantities identical to the other denominations.10 Therefore, we can use the quantities of other small denominations issued between mid-1776 and mid-1778 to estimate the size of the gap in the paper $1 supply—a whopping 1,033,857 bills!11

Is anyone prepared to believe that a million or more pewter dollars (or even tens of thousands) were clandestinely produced around 1776-78 to take the place of the Continental Currency $1 bill?12 There is no doubt that the pause in $1 bill production was intentional, but it had nothing to do with a pewter substitute. Congress, with its fingers always on the pulse of the money supply, simply printed what it thought necessary for the financial health and convenience of the United States on an as-needed basis.13 Remember, too, that Congress printed 600,000 of each of the four fractional denominations of February 17, 1776, which were purposely designed to be easily combined to make an even dollar.14

Who “E.G.” Is Not

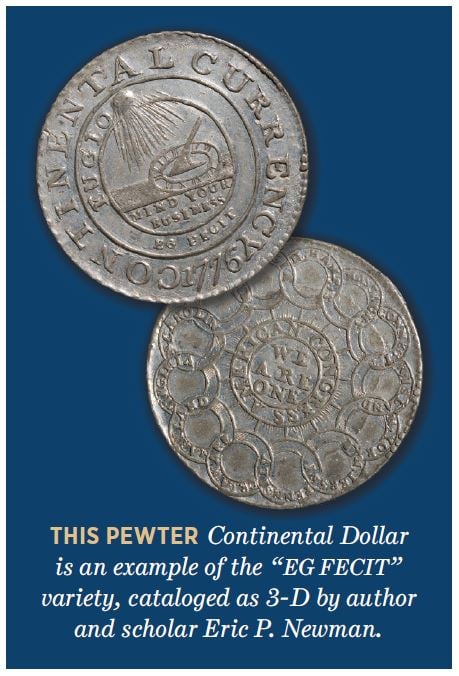

Among the most nagging questions pertaining to the Continental Dollar is the identity of the person whose initials appear on one obverse die. Baffling to 19th-century numismatists, the signature “EG FECIT” below the sundial on this variety15 was anonymously hypothesized in 1909 as being that of Ephraim Getz16; in 1952 Eric Newman suggested it might be Elbridge Gerry.17 (While this particular Getz doesn’t seem to exist, Gerry was, at least, a member of the Continental Congress.)

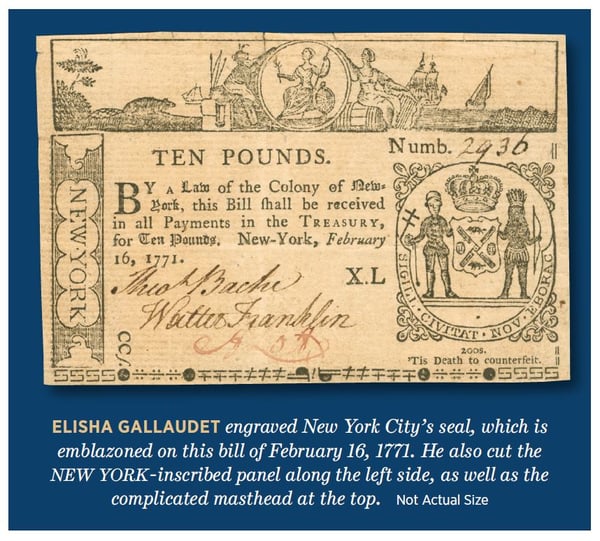

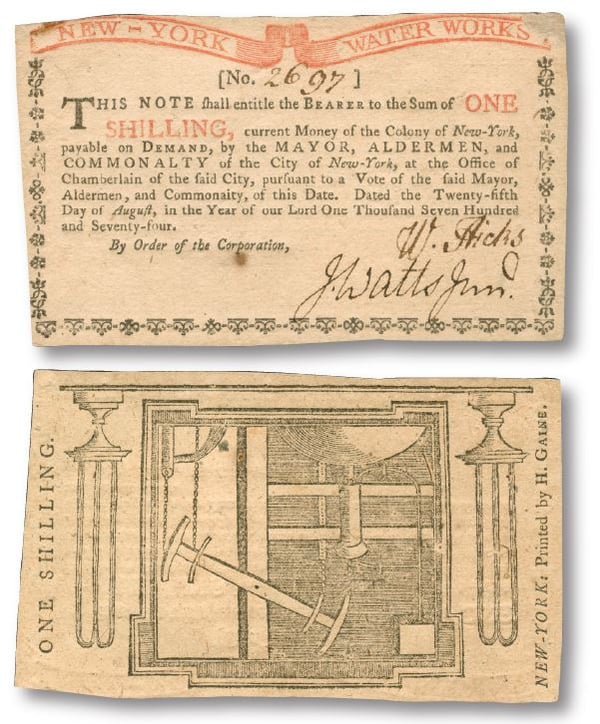

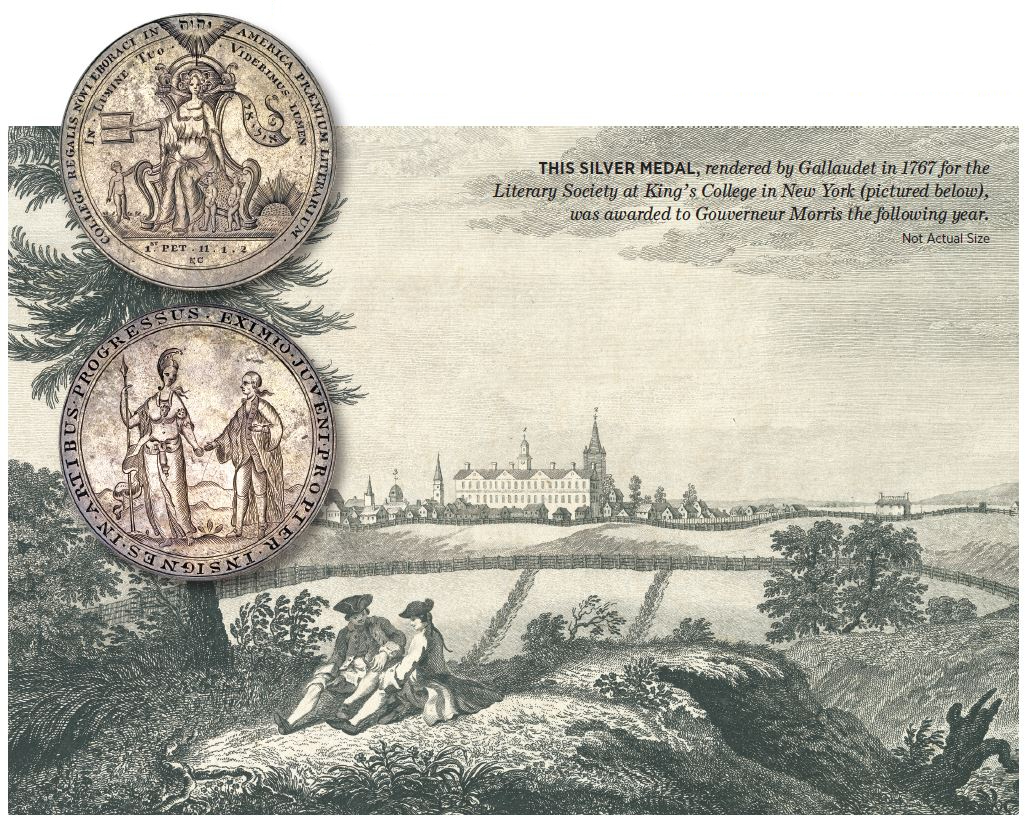

Shortly thereafter, Newman identified another “EG” candidate: New York City engraver Elisha Gallaudet, who was born sometime between 1728 and 1730. Newman, in his 1959 article18, did a superb job of bringing the pre-Revolutionary War works of Gallaudet to light. Documentary sources prove that he created components of the plates used to print the February 16, 1771, issue of New York’s paper money, as well as the tooling needed for the production of the 1774-76 issues of New York City’s “Water Works” notes. Other engravings that bear Gallaudet’s signature include a number of competently executed bookplates and a not-so-great portrait of George Whitefield19, one of the famed British clerics of the day. Head and shoulders above all these are the beautiful, individually engraved silver award medals he produced for the Literary Society of King’s College in 1767.20

▲ Known as "Water Works" notes, New York City issues of 1774-76 were printed from composite plates featuring cuts likewise created by Gallaudet. Photos: The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation/Gift of the Lasser Family (1994-210, 565 [New York] & 1994-218, 567)

Little else has been revealed about Gallaudet. He and his large family disappeared from New York City sometime after the mid-1770s and reappeared in Freehold, New Jersey, where he died in 1779.21 It has been reasonably posited that Gallaudet fled the British, who took New York City in mid-September of 1776, suggesting he was sympathetic to the Patriot cause. Could he be the “EG”-initialed tradesman with whom Congress sought a contract?

Nope. You guessed it…Elisha Gallaudet’s name doesn’t appear anywhere in the 14,000+ pages of the Continental Congress’ records. In contrast, this same archive records payments to those responsible for every aspect of the creation of the paper bills. Included are those who fashioned the special paper-making moulds, those who made the paper, the party who supplied the original border “cuts,” and the famed duo of Hall & Sellers, who did the actual printing.22 Congress even recorded payments to those who transported large quantities of fresh currency around the country for distribution.

Other than having initials that match those on the metal issue and the skill set necessary for cutting coin dies, what connects Gallaudet to the Continental Dollar and the Continental Congress? The answer is “nothing.”23 Then again, now that we know the hard evidence points to the pieces being produced across the ocean some four years after Gallaudet’s death, why should this misunderstood man be associated with them anyhow?

At the conclusion of “The Continental Dollar of 1776 Meets Its Maker,” Newman listed a dozen points he believed carried his argument over the goal line. From today’s perspective, some of them still ring true, but every factual statement he makes is tangential to the question at hand. Other points are purely conjectural, speculative or anecdotal and now can be disproved.

Thus, the question posited in Newman’s 1959 article has been addressed. The problem of identifying the maker of the Continental Dollars has not been solved, largely because “EG” had been sought in the wrong decade and on the wrong continent.

▲ This silver medal, rendered by Gallaudet in 1776 for the Literary Society at King's College in New York (pictured above) was awarded to Gouverneur Morris the following year. Photos: Stack's Bowers Galleries (medal) & The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation (museum purchase, 1968-440)

Poems, Pewter Dollars & Poppycock

More recently, other bits of potentially relevant information have appeared in support of the Continental Dollar as a circulating Revolutionary coin of 1776. These include two tales of an American mint and its purported products. The first, appearing in the June 26, 1776, issue of The New York Journal, is nothing more than a rumor that made it to the newspaper’s offices, as declared by the article’s opening phrase:

We hear it proposed, that after three months, the currency of all copper coin made of bad metal, or wanting in weight, is to pass at the rate of 15 for an eighth part of a dollar. And if it shall appear that there is not a sufficiency for common use, that it will all be called in, and a new impression struck of a Continental Copper Coin, of a larger size; twelve of which is to pass for a dollar, after which no other coppers are to pass current.

As this tale of a proposed policy change went no further, the story was quickly deemed baseless by the publisher. The second reference, little more than a snippet of transatlantic gossip, appeared in the December 26, 1776, issue of The London Chronicle. Writing home from New York City, an anonymous British officer told his unnamed correspondent that

the Congress have established a Mint at Philadelphia, where they coin copper and silver pieces about the size of a half a crown: In silver go for twelve shillings, in copper for fourteen pence.

As with The New York Journal piece, this account was never revisited or continued, showing that it also was ultimately judged to be untrue. From a numismatic point of view, neither account describes a piece even remotely similar to a circulating pewter Continental Dollar.24 While interesting, these rumors add nothing to our pursuit.

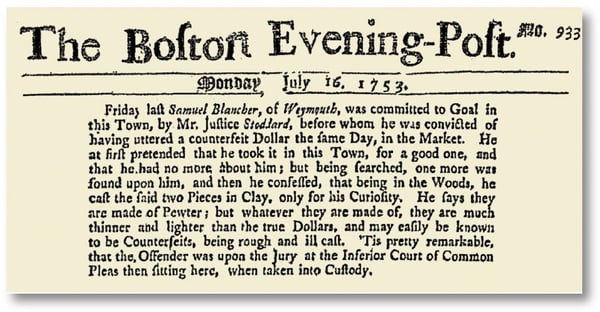

▲ This excerpt from the Boston Evening Post on July 16, 1753, relates the story of Samuel Blancher, who was jailed for casting and spending counterfeit pewter dollars. Below is a fake Spanish "Pillar dollar" which was found in Crown Point, New York, at the site of an 18th-century military post. Photos: Don Troiani Collection (Counterfeit) & Erik Goldstein Collection

The most recent piece of fresh evidence offered in support of the Continental Dollar appeared in “18th Century Writings on the Continental Currency Dollar Coin,” which Eric Newman co-authored with Maureen Levine in the July 2014 issue of The Numismatist. This extensive article led off with an investigation of Jonathan Odell’s satirical poem “The Congratulation.” Odell, a New York Loyalist, penned its verses in 1779 to denigrate the Continental Congress and its currency, while provoking those negatively affected by it. Without rehashing Newman and Levine’s words about Odell, or presenting another transcription of the entire poem, we’ll cut to the chase here. The final stanza, lines 13-16, read:

Whoever these important points

explains,

Congress will nobly pay him for his

pains,

Of pewter dollars, what both hands

can hold,

A thimble-full of plate, a mite

of gold…25

.jpg?width=263&name=fake%20spanish%20pillar%20dollar%20(1).jpg) In the next few sentences, Newman and Levine speculated on the meaning of the blatantly generic phrase “pewter dollars” and concluded, without offering any supporting evidence, that it must be a reference to a circulating Continental Dollar.

In the next few sentences, Newman and Levine speculated on the meaning of the blatantly generic phrase “pewter dollars” and concluded, without offering any supporting evidence, that it must be a reference to a circulating Continental Dollar.

Pewter dollars were indeed common in 18th-century America and appear in both documentary and archaeological records.26 But they aren’t Continental Dollars. They are locally produced counterfeits of the common Spanish colonial dollar, a fact not offered for consideration by the article’s authors. A search through early newspapers yields numerous accounts27 of these treasonous coins, including this blunt warning in the April 16, 1759, edition of The Boston Evening-Post:

The Public are cautioned to beware of counterfeit Dollars, for such there are passing among us; they are made of Pewter, and may be easily distinguished from the true ones.

Odell’s caustic words aren’t a smoking gun at all. Rather than supporting the notion of the Continental Dollar as a circulating coin of the War of Independence, the poem merely alludes to a now-fascinating set of crimes that plagued commerce in Early America.

Speculation Spawns “Attribution Creep”

A review of what has been written about the Continental Dollar since Newman published his hypothesis in 1959 shows a resounding acceptance of its tenets. What was presented as a circumstantial case for the identification of Gallaudet as the creator of an undocumented metallic replacement for the Continental Currency $1 bill had petrified into irrefutable fact. This phenomenon, in addition to helping subvert objectivity and the hunt for additional facts, has spawned another significant misattribution.

Consider the fractional specimens of the February 17, 1776, issue of Continental Currency, which bear designs borrowed by the maker of the Continental Dollars about seven years later. The crediting of these pewter pieces to Gallaudet has caused more than a few authors to follow a false path of logic and to conclude that he must also have been responsible for the cuts needed to print the fractional bills. Once again, the proceedings of the Continental Congress slam the door shut on a modern theory. In the records, no names are associated with this one-time issue. Newman knew this in 195928 and captioned the $ 1⁄6 bill pictured in his article as “made by an unidentified artist.” The “facts” had morphed long before the Newman/Levine article was published in the 2014 volume of The Numismatist. Without offering supporting evidence, the authors stated that Gallaudet

had engraved the 1771 New York State currency, the 1774-76 “New-York Water Works” notes and the February 17, 1776, Continental Currency one-sixth dollar paper currency. The engravings for the dies for the 1776 dollar coin clearly are based on the design on the one-sixth dollar bill.29

I wonder which came first—the circumstantial chicken or the speculative egg? We know the “EG” who made Continental Dollars around 1783 was not Gallaudet, who had died years before. Therefore, this attribution can’t be forced on the 1776 fractional bills. Until more facts are uncovered, all we know is that they were printed from plates incorporating cuts created by an unknown artisan.

▲ The Continental Congress, represented here (from left) by John Adams, Gouverneur Morris, Alexander Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson, conducted most of its business in Philadelphia, contracting production of its paper money to local tradesmen. Illustration: Library of Congress/Augustus Tholey

The Way Forward

It is always healthy to question the conventional wisdom regarding past events, places and things, especially now that researchers have some pretty powerful tools at hand. The digital era has made it possible to discover many needles hidden in institutional haystacks around the world, often from the convenience of one’s favorite comfy chair. We owe it to ourselves, and those who come after us, to perpetually ferret out new truths about the numismatic treasures we love. Yes, the process of discovery is electrifying, but it also can be painful, as beloved old beliefs stubbornly lurch into the realm of mythology. Nevertheless, it’s always better to keep it real, isn’t it?

▲ This pewter Felicitas Britannia et America medal (Betts-614) was struck in England in late 1783. Its reverse design is the same as most Continental Dollars, and the piece features a milled edge. Photos: The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation /Gift of the Lasser Family (2008-46, 172 [Medal]) & Trustees of the British Museum/Dr. Catherine Eagleton

Having set out to replace erroneous and presumptive statements about the Continental Dollar with provable truths, I have taken this study as far as possible for now. Many questions cannot be answered at this point. In the absence of hard evidence, any further hypotheses could lead to a fresh layer of theoretical baloney. I want to avoid this at all cost, so I offer no speculation here.

Instead, I’d like to encourage the pursuit of additional facts by posing a few queries. Some of these relate to flawed suppositions of the past and might seem rhetorical or, at best, the beating of dead horses. Regardless, exploring them could prove to be a useful and enjoyable exercise in critical thinking… and therefore worthwhile. As possible answers and clues arise regarding the following, they surely will bring fresh questions:

- Who was “EG,” the person who created at least one Continental Dollar obverse die? Now that we know the search has long focused on the wrong side of the Atlantic, we can begin to look for him in 1780s England or Europe.

- As off-metal strikes of a common pewter medal, did the brass and silver examples play a historic or numismatic role?

- Other than the explanatory flyer saved by Sarah Sophia Banks (an artifact that now resides in the British Museum), do other examples exist and are they identical to hers?

- How do these Continental Dollar medals relate to the pewter “Felicitas Britannia et America” medals (Betts-614) struck in England after September 1783? Not only do the two share a common reverse design and lack a copper “scavenger,” but both also have milled edges, making them strikingly similar.

- Can the dies used to impress the edges of the Betts-614 medals be linked to those used on any varieties of the Continental Dollar?

- Does evidence exist to support the use of an edge mill in America before 1777?

- Why do no Revolutionary War-era newspapers mention a circulating, Congressionally authorized pewter dollar? This absence stands in stark contrast to the innumerable times that diverse aspects of Continental paper money were discussed. Money was as fascinating to newspaper readers then as it is now

- Why have none of these pewter pieces been excavated from campsites occupied by the Continental Army during the Revolutionary War? Collectively, these sites have yielded thousands of pewter buttons and countless copper and small silver coins. Since one of the main purposes of the Continental Currency was to pay troops, huge quantities of the money went directly to the military. One would think if a Congressionally sanctioned pewter dollar circulated after mid-1776, then a good place to look for a lost or discarded example should be the site of a Continental Army encampment, home to thousands of soldiers for months or years on end.

- The Continental Congress conducted a majority of its materials-based business in the Philadelphia area, and its paper money, from A to Z, was produced by local tradesmen. Though David Rittenhouse supplied the first 36 “cutts”30 for the Continental Currency plates in 1775, we don’t know who supplied those employed for the February 1776 fractional bills. However, other convenient options existed. Philadelphia had many of the best engravers and metalworkers in 18th-century America, like James Smithers, who made cuts for some currency issues. Other highly skilled mechanics, like silversmith Joseph Richardson, produced the dollar-size 1756 “Kittanning Destroyed” and the 1757 “Treaty of Easton” medals, the first such items struck in British America. Even the dies Richardson used were Philadelphia-made, from the hand of clockmaker Edward Duffield. One might wonder why the Continental Congress would turn to Gallaudet in New York City, a hundred miles and a few days’ travel away, when it had a plethora of more talented craftsmen with a greater array of skills right in its backyard.

- The suggestion that the Continental Congress was producing coins in secrecy to avoid trouble with the British makes no sense. Other far more “treasonous” activities were extensively documented in its records, like the active support of rebellious troops (the Continental Army) and the issuance of “Letters of Marque,” which authorized patriotic American sea captains to prey on British shipping anywhere in the world. While Congressionally licensed pirates were a clear and present danger to Great Britain, the striking of base-metal coins during wartime posed no threat to the Crown Forces or the empire’s economy. And would the production of such coins be deemed more treasonous than the printing of Continental Currency or, for that matter, the dispatching of the Declaration of Independence to King George III?

ACknowledgments

For their assistance and inspiration, I wish to thank Jason Copes, John Dannreuther, Dr. Catherine Eagleton, Jimmy Hayes, Ronald L. Hurst, John J. Kraljevich Jr., Angelika Kuettner, the late Joseph R. Lasser, David McCarthy, Chris McDowell, the late Eric P. Newman, Dr. Joel Orosz, Ray Williams and Vicken Yegparian. ■

NOTES

1 Now and hereafter, the “Continental Dollar'' is not to be confused with the Continental Congress paper $1 bills issued between 1775 and 1780. The use of the term in this article is for convenience only and is not intended to suggest that the author accepts these numismatic items as coins.

2 The author unabashedly offers his mea culpa on this point.

3 Crosby, Sylvester S. The Early Coins of America, 1875 (Quarterman reprint, 1983), pp. 305-06.

4 See the January 2018 issue of The Numismatist (p. 54) for a complete transcription of Bishop Watson’s description of the Continental Dollar, and Meigs’ refutation in the December 12, 1788, issue of The New-Haven Gazette and the Connecticut Magazine.

5 The authenticity of the “1776” coppers, mainstays of the “Red Book'' for generations (2018 edition, pp. 59-60), has come under serious question in the past few years. Though Crosby, believing them to be authentic, also discusses them (pp. 175-76, 30305), an examination of these enigmas is a fracas for another day.

6 “British-American Colonial Coins,” p. 250.

7 du Simitière, Pierre Eugene. Common Place Book, 1775-1784, Library of Congress, Manuscript Division. See the aforementioned article in the January 2018 issue of The Numismatist (p. 51) for an analysis of du Simitière’s writings.

8 Fractional denominations of February 17, 1776, excluded.

9 Newman, Eric P. Early Paper Money of America, 5th edition (2008). The quantities were determined by the composition of the printing plates, with eight different denominations of bills on each sheet. See p. 459 for a discussion of this aspect of paper money manufacture.

10 A combined total of 267,991 Continental $1 bills were generated by the January 1779 and the April-July 1780 guaranteed issues. See Newman (2008), op. cit., pp. 73, 177, 215, 245, 263, 291, 358, 400 and 452.

11 This number is the total quantity of bills issued for each denomination ($2, $3, $4 and $5) during the time the $1 bill was not produced. See Newman (2008), op. cit., pp. 66-69.

12 Since no hard, primary-source evidence suggests the existence of a covertly operated mint, why should we assume one was established solely for the sake of legitimizing the Continental Dollar as a circulating coin?

13 It also must be noted that not every denomination was represented in every issue of Continental Currency, with the exception of the $5 bill. The $2 and $3 bills were omitted from both issues of 1778; no $4 bill was included in the September 1778 issue; and the $6 permanently disappeared after the April 1778 issue. The $20 bill, initially worthy of marble-edged paper, disappeared after May 1775, only to be reinstated in a more economical format in April 1778. Based on the obviously deliberate manner in which the Continental Congress chose which denominations were to be issued during the course of the war, there’s no reason to think anything funny was going on.

14 The $ 1/6 , $ 1/3 , $ 1/2 and $ 2/3 bills can be combined in at least seven different ways to equal $1.

15 Newman, Eric P. “The 1776 Continental Currency Coinage,” The Coin Collector’s Journal, July-August 1952 (No. 44), p. 8, Obverse 3.

16 The Numismatist, June 1909, pp. 177-78. This article, published without a named author, probably was penned by Farran Zerbe, the magazine’s managing editor and publisher. The Getz bit is hearsay as reported to Zerbe by Edgar H. Adams.

17 Newman (1952), op. cit., pp. 3-4.

18 Newman, Eric P. “The Continental Dollar of 1776 Meets Its Maker,” The Numismatist, August 1959, pp. 914-26.

19 For a reproduction of Gallaudet’s engraving of Whitefield, see Newman (1959), op. cit., p. 922.

20 As detailed in Vicken Yegparian’s “The Literary Premium Medals Awarded by the Literary Society of King’s College in New York, 1767-1771.” This unpublished paper was delivered as a lecture at the October 2004 Coinage of the America’s Conference (COAC), hosted by the American Numismatic Society in New York City. It should be noted that these medals apparently were unknown to Newman in 1959 and were not mentioned in his work about Gallaudet.

21 The last will and testament of Elisha “Gillaudet” (sic) was dated March 29, 1779, and his estate inventory taken on June 11 of the same year was valued at almost £122. See New Jersey Abstract of Wills, Vol. XXXIV, 1771-1780, p. 204.

22 Payments to these tradesmen are recorded in the Library of Congress’ Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774-1789, Government Printing Office, 1909. Hall & Sellers printed the currency from plates incorporating cuts supplied by David Rittenhouse. The special paper used for the bills was made by Frederick Bicking using “moulds” fashioned by Nathan Sellers.

23 Two Gallaudets served in New Jersey regiments during the war. Contrary to rumor, neither has a documented connection to the Continental Congress, George Washington or pewter numismatic objects.

24 At this time, a British half crown measured about 33mm in diameter, far smaller than the average 40mm diameter of a Continental Dollar.

25 Odell, in citing quantities of these three metals, was referring to a miniscule amount of money.

26 See W.L. Calver and R.P. Bolton’s History Written with Pick and Shovel, New York Historical Society, 1950, pp. 74-75, for an image of a counterfeit pewter Spanish Colonial milled 8 reales (portrait type), excavated from a Revolutionary War camp near the northern tip of Manhattan Island.

27 For other primary-source accounts of circulating counterfeit dollars made of pewter, see the July 16, 1753, issue of The Boston Evening Post, p. 2 (illustrated here), for an especially detailed account of Samuel Blancher’s woeful situation. Kenneth Scott’s Counterfeiting in Colonial Pennsylvania, p. 100, and Counterfeiting in Colonial Connecticut, p. 189, include transcriptions of newspaper accounts dating to the 1760s and 1770s. Others can be found on the Internet database America’s Historical Newspapers (available by subscription only).

28 Newman (1959), op. cit., p. 916.

29 Over the years, Newman speculatively identified Gallaudet as the engraver responsible for the February 1776 fractional bills. Aside from the abovementioned 2014 article, see Newman (2008), op. cit., pp. 21, 64 and 284, for other appearances of this mistaken attribution.

30 Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774-1789, Vol. III, p. 286.

About the American Numismatic Association

The American Numismatic Association is a nonprofit organization dedicated to educating and encouraging people to study and collect coins and related items. The Association serves the academic community, collectors and the general public with an interest in numismatics.

The ANA helps all people discover and explore the world of money through its vast array of educational programs including its museum, library, publications, conventions and numismatic seminars.