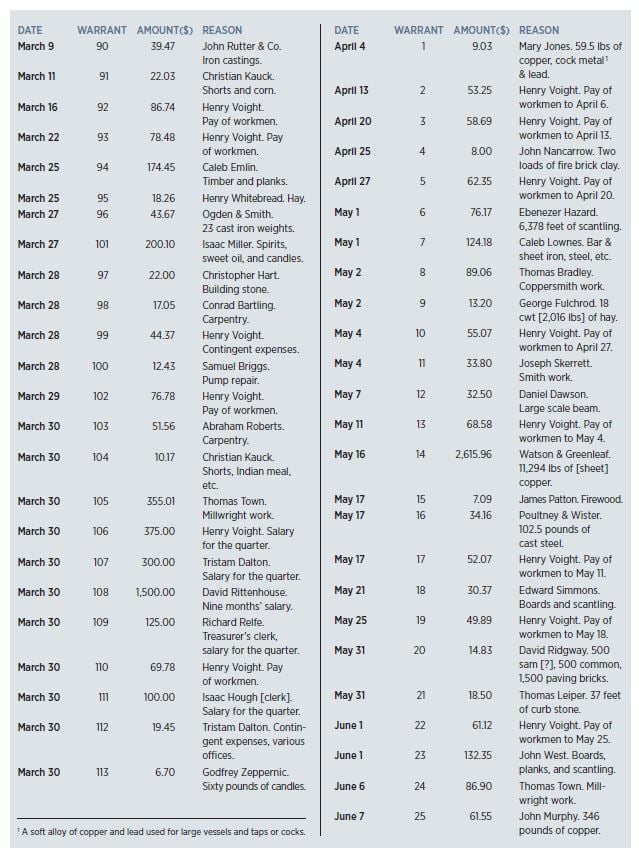

U.S. Mint Expense Warrants

Originally published in The Numismatist, December 2015

Accounting documents are critical to understanding the Mint’s affairs at the end of the 18th century.

The December 2012 issue of The Numismatist carried an article dealing with the contingent expenses of Chief Coiner Henry Voight in 1793. These were small cash expenditures for needed supplies, and the ongoing accounts were settled with Mint Treasurer Tristam Dalton at the end of each quarter.

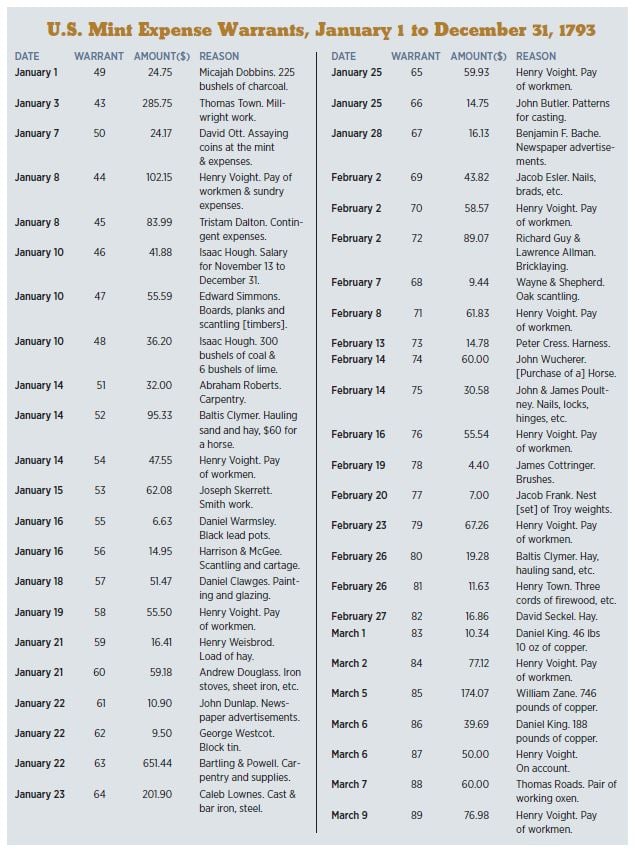

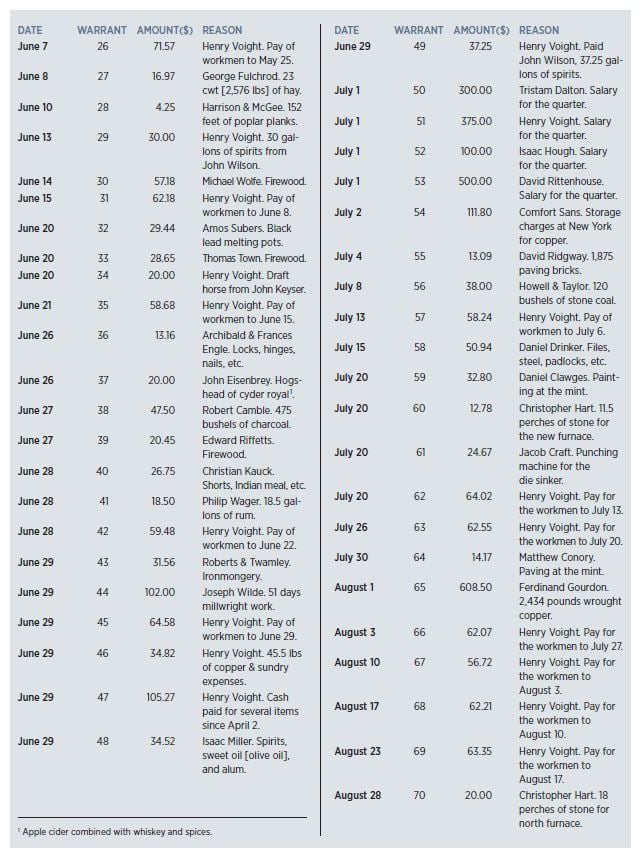

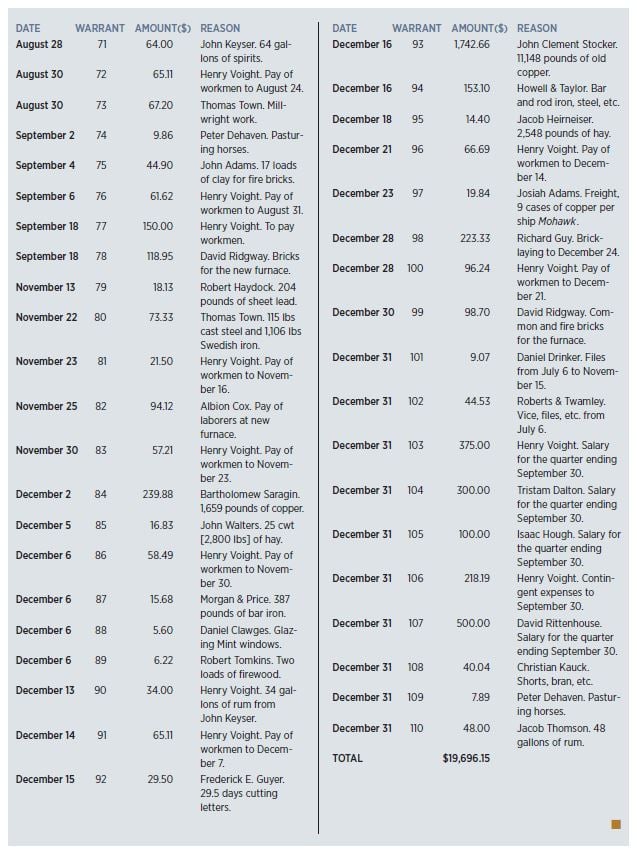

The present article deals with the expense warrants signed during 1793 by Mint Director David Rittenhouse. While the contingent expenses were usually for small sums, warrant payments were normally for larger amounts.

Records of the Mint for 1793 are relatively sparse, and the expense accounts are critical to understanding the state of affairs. Even though we have complete accounts of the monies spent in 1793, some questions still cannot be satisfactorily answered. It is known, for example, that Joseph Wright was appointed as the Mint’s first engraver, but he died during the 1793 yellow fever epidemic and was therefore never formally approved by the Senate. There are no pay records for Wright, but there should be, even for the limited time he worked at the Mint. In some cases, Mint employees, such as clerk Isaac Hough, purchased items for the Mint and were reimbursed through a warrant.

In the table accompanying this article, abbreviations such as “&” for “and” and “lbs” for “pounds” were used for space considerations. The term “cwt” means hundredweight, which in 1793 was equal to 112 pounds.

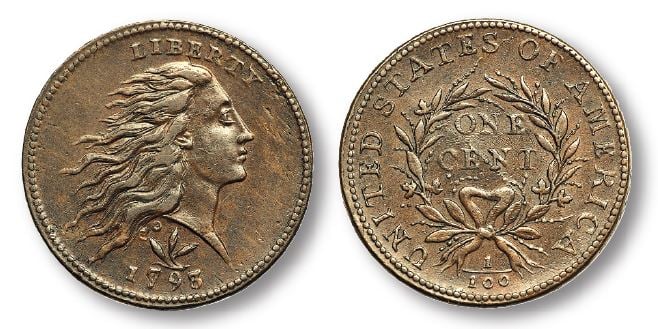

▲ THE WREATH CENT was struck from April to July 1793. Photo: Ira & Larry Goldberg Auctioneers

There is a gap in the warrants from September 18 to November 13, which coincides with the time that the Mint was closed due to the yellow fever epidemic; several thousand Philadelphia residents died in the outbreak of this dreaded disease. The Mint did not close down again until August 1797.

Officers and clerks of the Mint in 1793 included the following: David Rittenhouse, director; Henry Voight, chief coiner (and engraver pro tem until July 1793); Tristam Dalton, treasurer ; Joseph Wright, engraver (August-September); Robert Scot, engraver (November-December); Albion Cox, assayer; and Richard Relfe and Isaac Hough, clerks. Adam Eckfeldt, though widely believed by numismatists to have been an employee since 1792, did not become a full-time employee until late 1795, and there are no pay records for him in 1793.

Albion Cox’s position as assayer was somewhat special. He had been hired in England and arrived in Philadelphia to begin his duties in May 1793. His tenure in office, however, was considered to have begun in late February of that year, when he made the arrangement in London with American Minister Thomas Pinckney.

As the spelling of Voight’s name is sometimes controversial, it should be noted that he personally spelled it “Voigt” in internal Mint documents. Just about everyone else, including Thomas Jefferson and newspapers, used “Voight.” Even the Philadelphia City Directory entry for 1793 used the latter version. (The chief coiner also used the alternate spelling in public when appropriate.)

A new book, published in mid-2015, is worth recommending to readers interested in the early days of the Mint. The well-researched work by William Nyberg, Robert Scot: Engraving Liberty, for the first time has given Engraver Robert Scot his just due in terms of his fine engraving, both for coinage dies and line illustrations. Numismatic writers in the past have been somewhat dismissive of his talents, but

Nyberg shows us, with quality illustrations and text, the depth of Scot’s ability.

In 1793 workmen were paid weekly. Chief Coiner Voight was responsible for the workmen, at first including those later employed in the assaying department under Albion Cox. Until the end of March, the warrants for this purpose were signed by the director on the last day of the working week (Saturday), but the actual funds were not given to the workmen until a week later. Beginning in April, the warrants were made out at the time of payment, a week after the work week had ended. Workmen were paid directly in cash, unlike the other warrant expenses that were paid by checks written on the Mint account at the Bank of the United States.

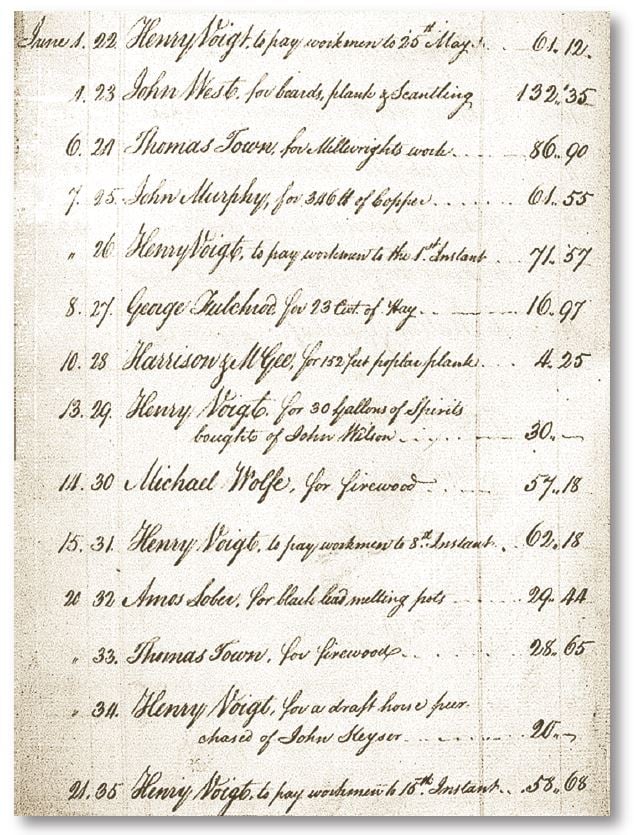

▲ A PAGE FROM the 1792-1817 Warrant Account Book. Photo: Ira & Larry Goldberg Auctioneers

Warrants for the first quarter of 1793, through March 30, were numbered consecutively from the first warrant issued in July 1792. The numbering began again at the beginning of April. Some of the later 1793 expenses and salaries were delayed until January 1794, however.

There are several entries concerning a furnace under construction. In 1793 copper was not melted into ingots at the Mint itself, but rather at a furnace a few blocks away. This was perhaps due to the acrid fumes involved in such work and the limited space available at the Mint’s principal Seventh Street location.

A portion of the warrants listed here was published by Frank Stewart in his 1924 book, History of the First United States Mint. Lack of space prevented him from listing all of the warrants, however. A few minor errors in the 1924 book, caused by miscopying, have been corrected in the present listing. Two of the recipient names appear to have been misspelled by the Mint clerk. The account book, from which these warrant records have been copied, show George Westcot instead of Wescott and Amos Sober in place of the correct Subers.

The reader will note the use of horses and the necessary feed for them. These animals, however, did not power the coining presses, but rather the rolling mills, which flattened the ingots down to coin thickness.

One of the most interesting expenses is found under December 15, when Ernest Frederick Guyer was paid $29.50 for cutting letters. These “letters” were, in fact, letter and date punches for Engraver Robert Scot, meant to be used in creating the working dies. It is therefore likely that the cents and half cents of 1794 were struck from dies using the Guyer punches. It is also worth noting that Guyer may have been the engraver of the 1792 half disme dies.

Acknowledgment

This article was made possible by a numismatic research grant from the Central States Numismatic Society. All of the warrant entries shown here are from the volume labeled “1792-1817” and located in RG 104, Entry 178, at the Philadelphia branch of the National Archives.

About the American Numismatic Association

The American Numismatic Association is a nonprofit organization dedicated to educating and encouraging people to study and collect coins and related items. The Association serves the academic community, collectors and the general public with an interest in numismatics.

The ANA helps all people discover and explore the world of money through its vast array of educational programs including its museum, library, publications, conventions and numismatic seminars.