Chaos and Calm on American Currency

We all make certain assumptions about money. We assume that there will be enough currency and coin to complete any transaction, that we can spend and receive money without difficulty or doubt, and that money will hold its value over short spans of time.

Americans of earlier eras couldn’t always make such assumptions, and that made commerce difficult in ways that are hard for us to imagine today. Several types of collectible currency serve as tangible reminders of our history, reflecting the political and economic turmoil of their times.

Britain’s American colonies often suffered from a lack of money, but the newly independent United States had the opposite problem – paper money issued by the Continental Congress and individual states during the American Revolution was so overabundant that they inspired the derisive phrase “not worth a Continental” The widespread issues carried inspirational inscriptions, such as “We Are One” (with imagery designed by Benjamin Franklin).

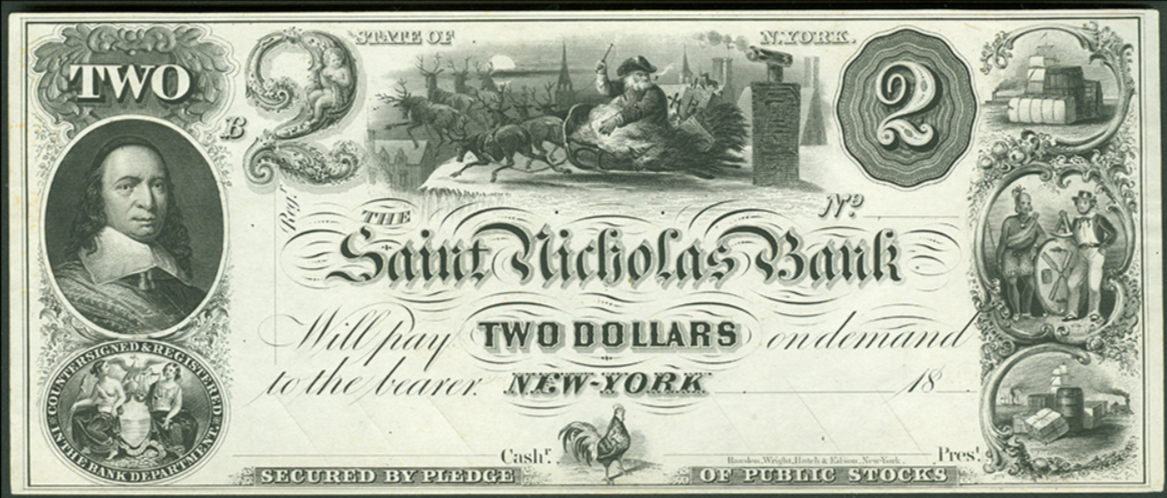

After independence and until the Civil War, thousands of banks issued their own paper money. These “obsolete bank notes,” as they now are known, featured a wide variety of interesting vignettes, including Santa Claus. But some users ended up with the economic equivalent of a lump of coal, because insolvent banks and frequent forgeries made commerce a challenge. The unsatisfactory system came to an end in 1863, after which banknote issues were standardized and financially regulated in the form of National Bank Notes.

▲ $2 Obsolete Bank Note, c. 1855 | St. Nicholas Bank, New York City

Paper money became especially important during the Civil War because of the conflict’s extreme financial demands. Many Confederate notes promised payment “two years after the Ratification of a Treaty of Peace between the Confederate States and the United States,” but as the South’s prospects dimmed, the notes’ value plummeted. The Union’s currency also caused inflation, and the resulting hoarding of coins led to the issue of compact “fractional currency” to replace small change.

Since the Civil War, all U.S. currency has originated with the federal government. American currency issues since 1929 are collectively known as “small-size” notes, because their familiar, 6.14 x 2.61-inch format is approximately 30-percent smaller than earlier, “large-size” issues.

For decades after the Civil War, there were as many as seven types of paper money in circulation. All of them remain legal tender, though today one type is universal (Federal Reserve Notes) and the rest are the domain of currency collectors. When first issued, their varying legal bases and eclectic financial underpinnings went largely unnoticed – a 1927 publication noted that “the various forms of paper are accepted as money with equal readiness … and present no particularly distinguishing features to the casual observer.”

But of course, numismatists are more than casual observers of money, and know better than to accept things at face value. Here’s a census of the various types of money that have circulated since the Civil War – distinguishable in part by the different colors of the printed Treasury seals they carry.

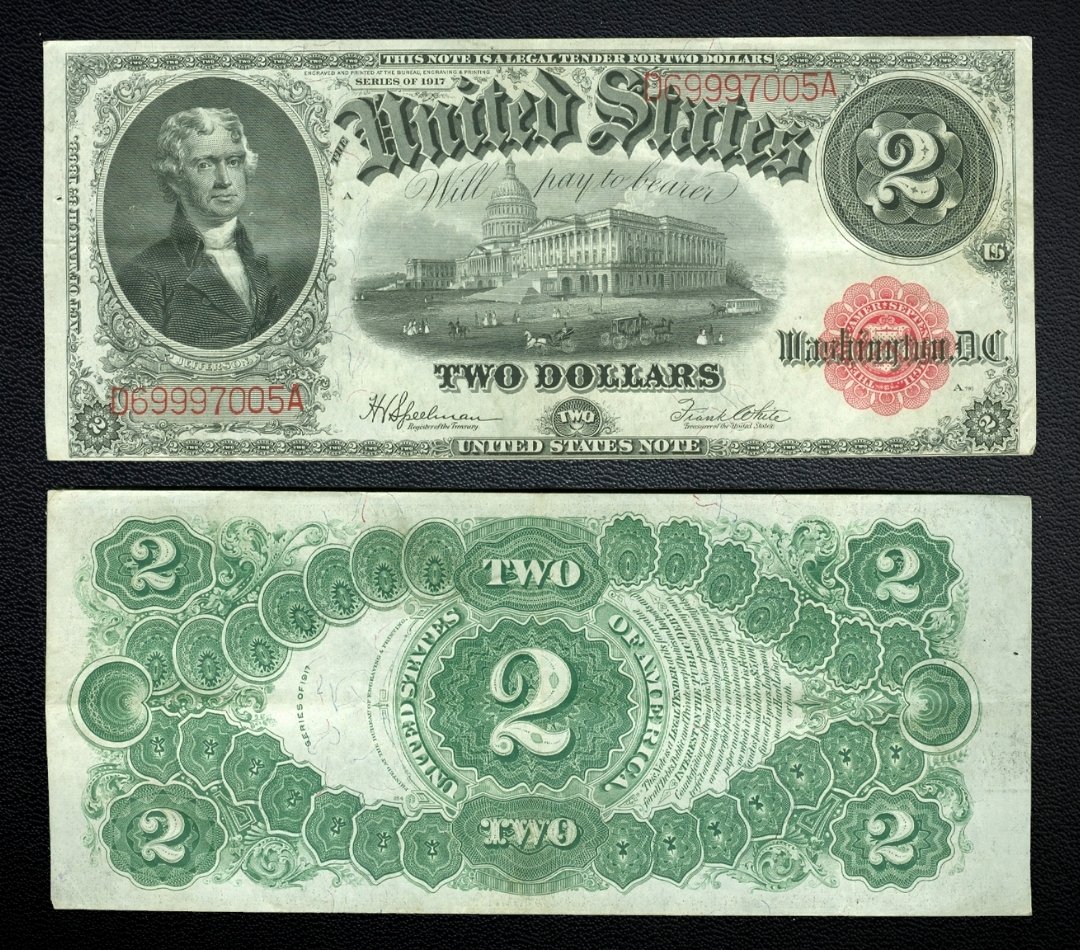

United States Notes, the original “greenbacks,” were originally issued as an emergency measure during the Civil War to pay the Union’s mounting bills – in the process, driving gold and silver temporarily out of circulation. But by the 20th century, United States Notes were a stable part of the money supply.

United States Notes, the original “greenbacks,” were originally issued as an emergency measure during the Civil War to pay the Union’s mounting bills – in the process, driving gold and silver temporarily out of circulation. But by the 20th century, United States Notes were a stable part of the money supply.

▲ 1917 Legal Tender Issue, $2 United States Note

Gold Certificates and Silver Certificates of various denominations were essentially receipts for precious metal coins held in Treasury vaults (or, in the 1960s, silver granules), and were redeemable as such. Gold certificates made large transactions more convenient, while silver certificates enabled a monetary role for otherwise unwanted Morgan and Peace Dollars. In the mid-20th century, Silver Certificates with their blue seals were the dominant type of $1 bill.

▲ $100 National Gold Bank Note, Nov. 30, 1870, First National Gold Bank San Francisco, CA

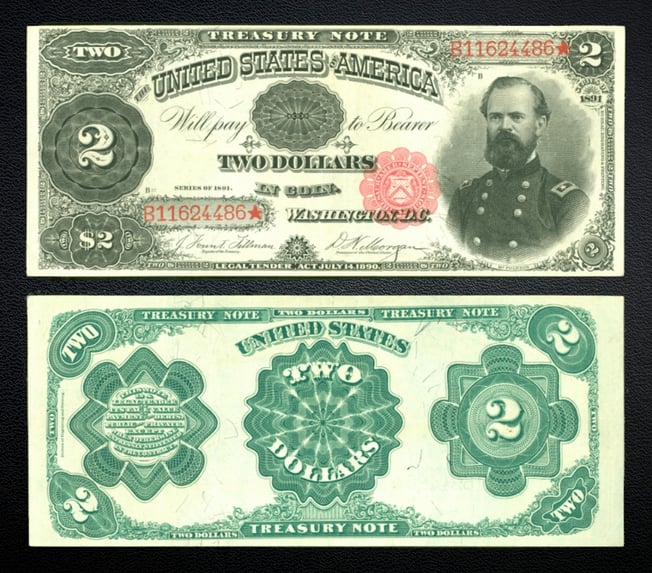

Treasury Notes of 1890 were used to accelerate the Treasury’s purchases of silver bullion (which had been required since the Bland-Allison Act of 1878, mandating that the United States Mint purchase millions of ounces of silver each month, to be coined into Morgan Dollars). Treasury Notes were redeemable “in coin” – the type of coin not being specified. The drain on gold and ensuing financial panic led to the end of these notes, and the cessation of silver purchases, in 1893.

▲ 1891 $2 Treasury Note

National Bank Notes were issued by government-chartered private banks that met certain financial criteria. The National Banking system was in place from 1863 to 1935, replacing the previously chaotic system of loosely regulated (at best) banknote issues by state and private banks. National Bank notes had standard designs, customized to include the name of the issuing bank. More than 12,000 banks issued notes, making a piece of hometown currency a distinct possibility for most collectors.

▲ $2 (Lazy Deuce) National Bank Note, 1st Charter Period, Series of 1875, Merchants National Bank, Salem, MA

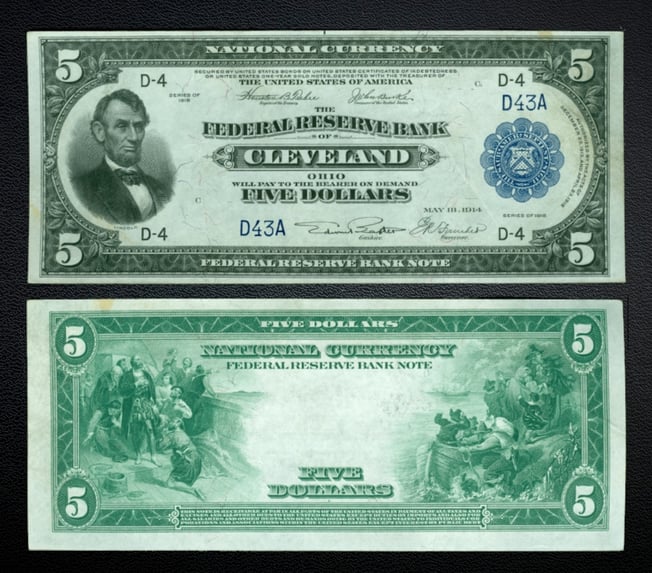

Federal Reserve Bank Notes are similar to National Bank Notes, the “bank” being one of the 12 branches of the Federal Reserve. They tended to be stopgap issues: after World War One when silver supplies were depleted by the Pittman act, or during the cash shortage of the Great Depression.

▲ 1914 $5 Federal Reserve Bank Note

Federal Reserve Notes were first issued in 1914, one year after the creation of the Federal Reserve System. The nation’s central bank was designed to provide stability and flexibility for the money supply. As the connection between paper money and precious metals was dismantled in the 20th century Federal Reserve Notes gained in importance, and since 1971 they have been the only type of currency issued.

Each Federal Reserve note is issued by authority of one of system’s twelve regional branches. The issuing branch used to be displayed prominently on each banknote. But these days only the one-dollar bill names the issuing bank; on other banknotes, the only designation is in the 2nd letter of the note’s serial number, where each letter corresponds to a different branch.

America’s history unfolds on the diverse large-size issues of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, with portraits of prominent people and vignettes of historical scenes. The artistry of American paper money reached its zenith with the “Educational” $1, $2 and $5 silver certificates of 1896, which featured allegorical representations of history, technology and commerce. Other interesting images include five Morgan dollars on the Series 1886 $5 silver certificate, a bison on the Series 1901 $10 U.S. note, and the battleship New York on the Series 1918 $2 Federal Reserve Bank note.

Small notes have their share of history as well. Some issues during World War Two were overprinted on their backs with HAWAII in large block letters. This ominous labeling would have enabled the notes to be easily demonetized if the islands had been occupied during the conflict. And on issues of the past two decades, you can see the evolution of technology in the form of anti-counterfeiting measures, including microprinting, color-shifting ink, and, on the $100 note, a hologram that give the appearance of three-dimensional motion.

▲ 2013 $100 Federal Reserve Note

Collecting currency issues from the present day and from earlier eras, and learning their stories, is a great way to make a tangible connection to American history.

About the American Numismatic Association

The American Numismatic Association is a nonprofit organization dedicated to educating and encouraging people to study and collect coins and related items. The Association serves the academic community, collectors and the general public with an interest in numismatics.

The ANA helps all people discover and explore the world of money through its vast array of educational programs including its museum, library, publications, conventions and numismatic seminars.